Village Portrait - 2004

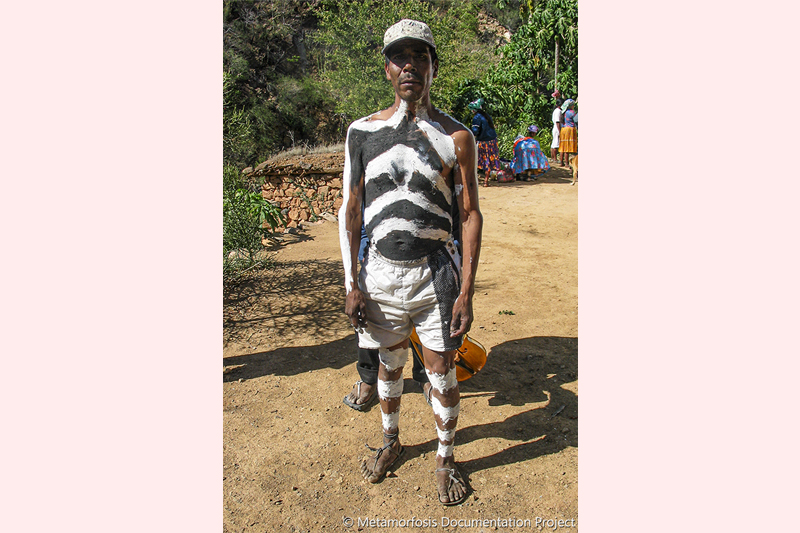

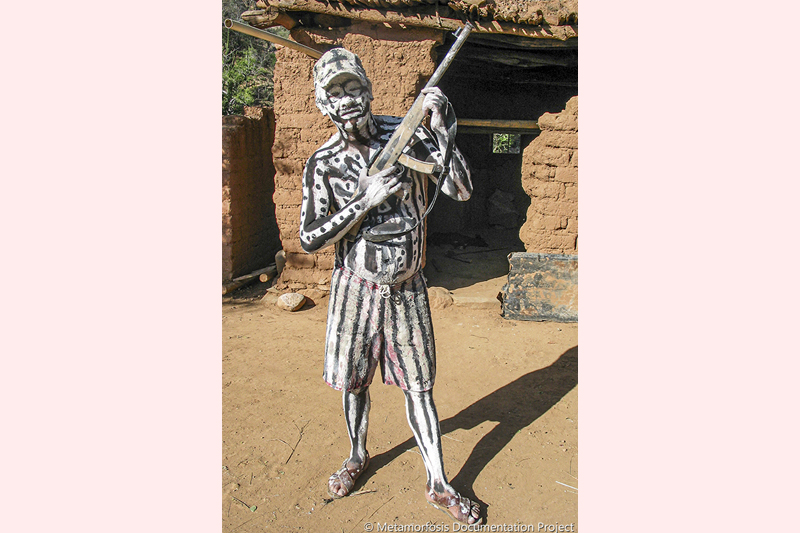

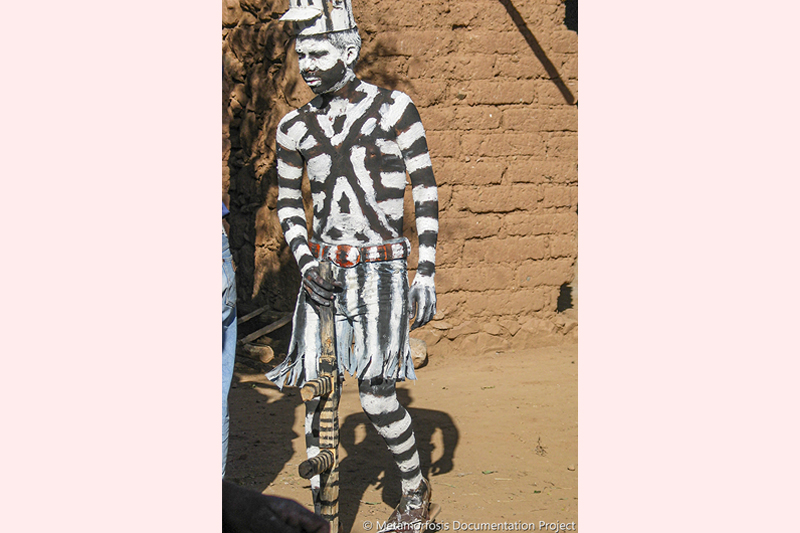

Devils and Soldiers

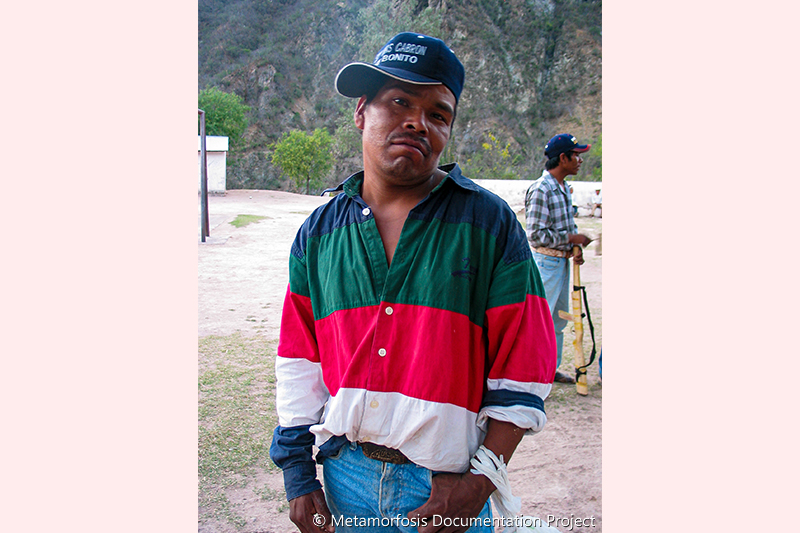

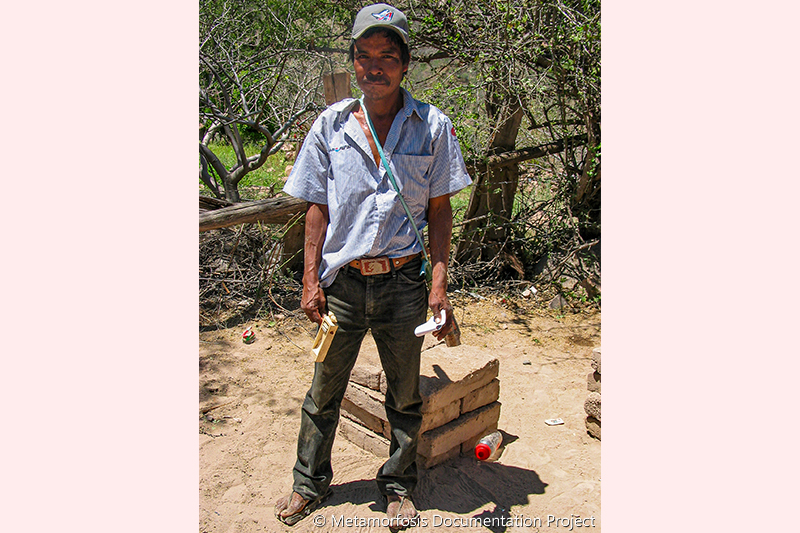

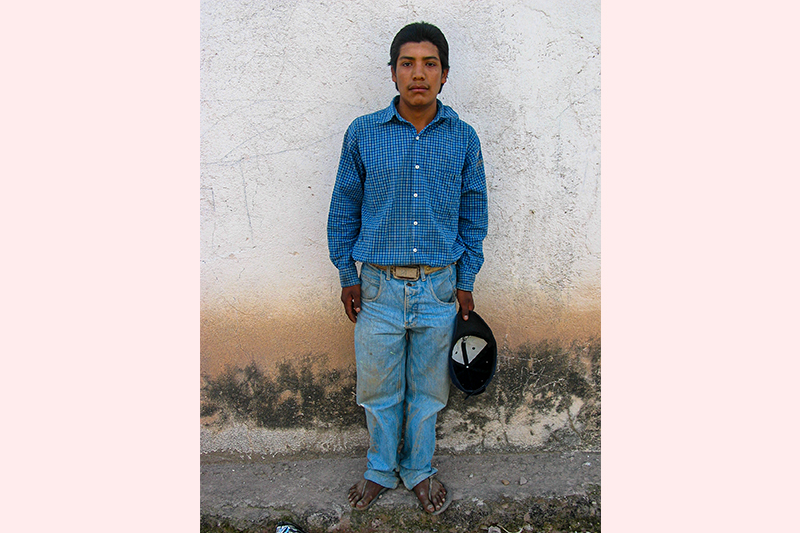

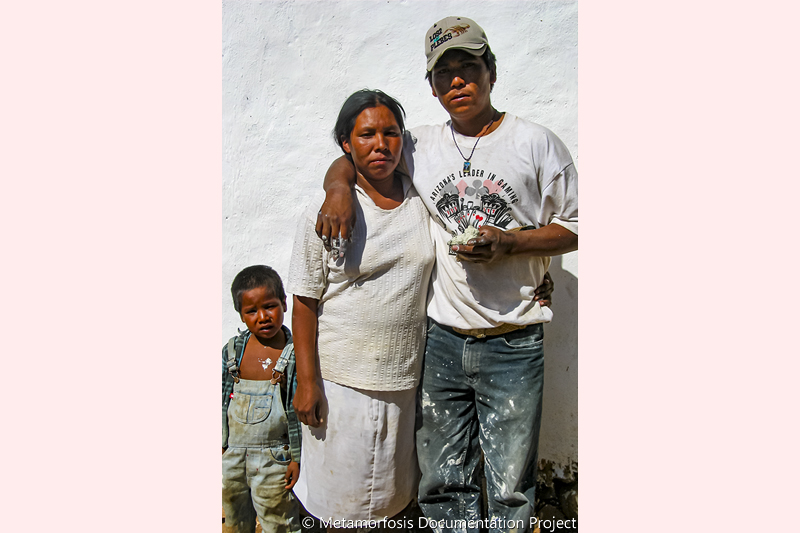

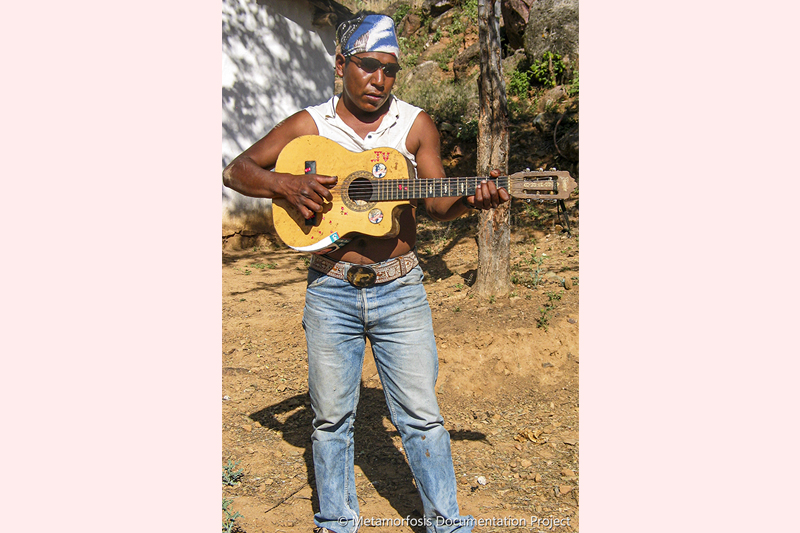

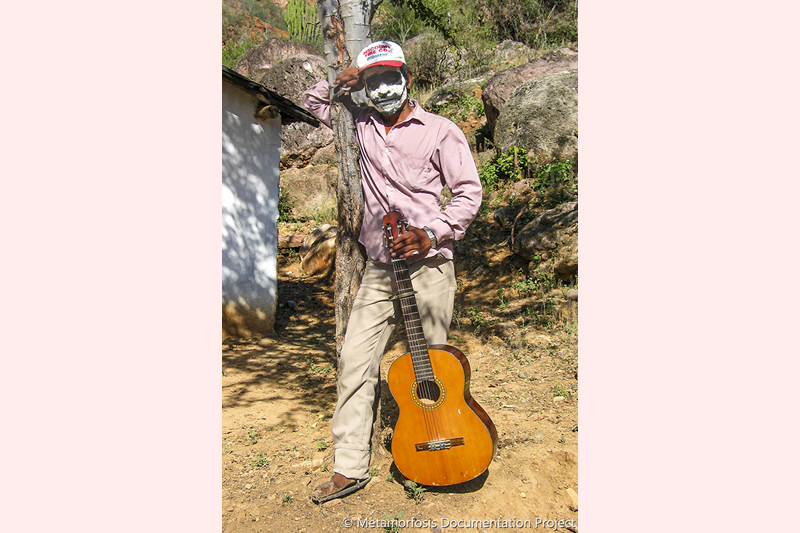

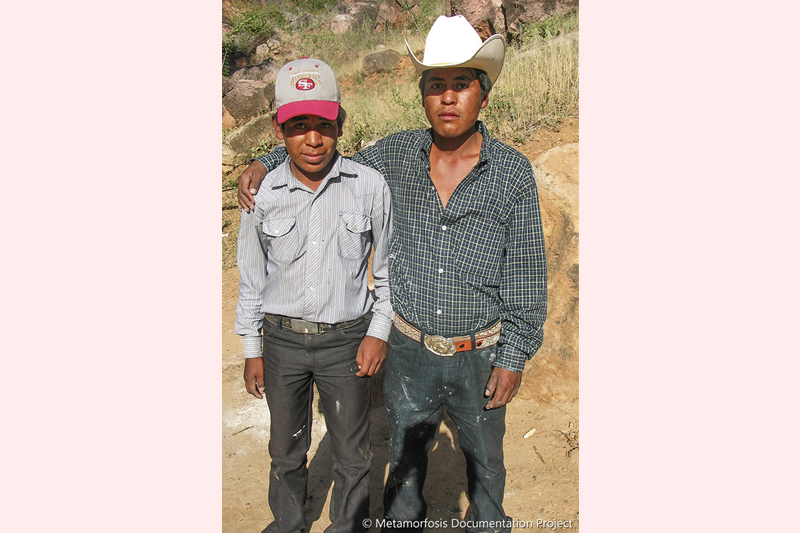

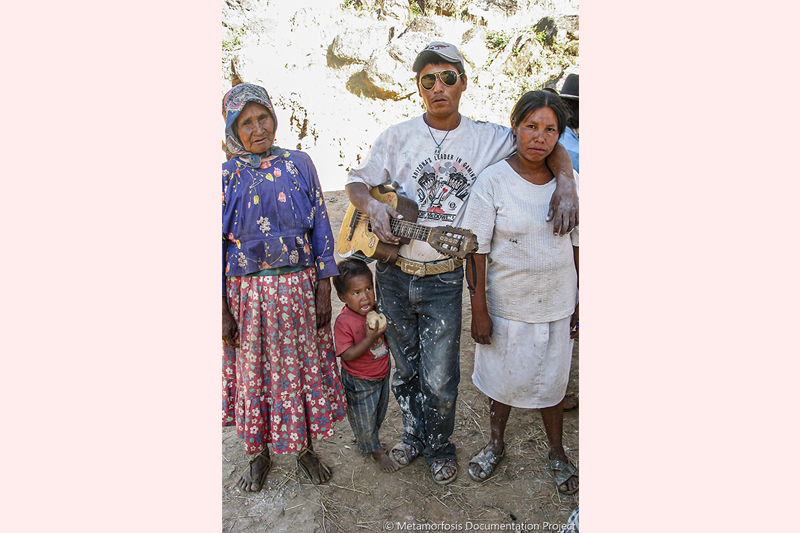

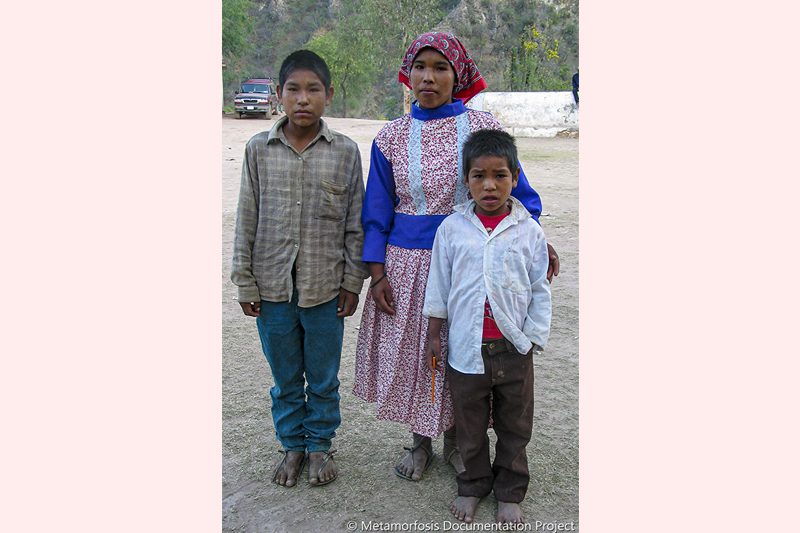

The People

"Yo No Conozco a Nicolás"

All these photos were taken in a small village in the Sierra Madre Occidental in north central Chichuahua in Mexico. This Tarahumara village is on the verge of assimilation by the modern and mestizo culture of Mexico and is currently threatened by the industrial expansion of mining and drug trafficking.

The photographic documentation of this village came about as an offshoot of an art project which documented post-colonial dances in this and other villages in Mexico and New Mexico.

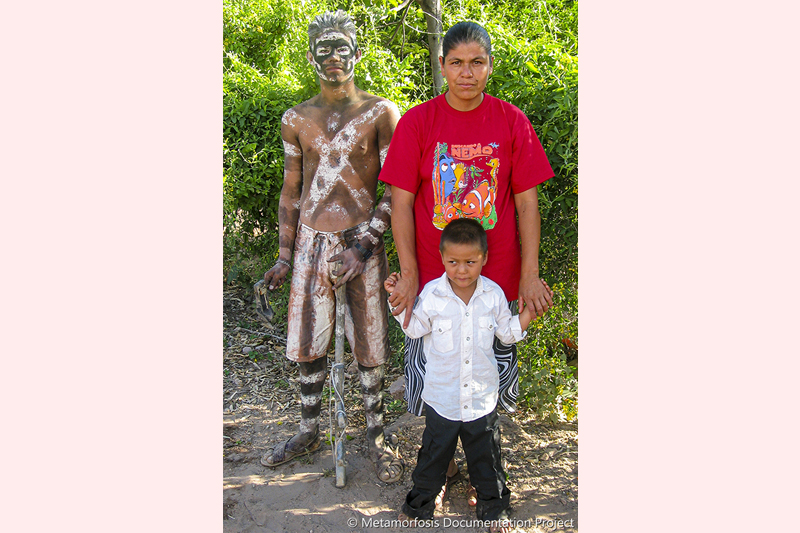

It is Holy Week, days before Easter. It is the time of danger, of sexual transgression; Christ is dead and the devils roam the town. Judas' effigy is out and about with his sons, the devils. No longer human, their bodies painted in black and white, they create havoc.

The soldiers defend the church from the advances of the devils, and the drama of the struggle between good and evil takes place.

It continues all afternoon and all night with mock battles, wrestling matches and the constant sound of the drum. Fasting, lack of sleep and the ritual drinking of tesgüino transport the participants of the ceremony to a deep altered state, and the confusion of the time of danger prevails. Saturday at midday the devils finally enter the church, which has been flooded with water. As the women sing the rosary, the devils roll on the floor and wash the paint off their bodies; they once again become human. In a frenzy, they exit the church and join the soldiers in destroying and burning the effigy of Judas. Once more good has triumphed over evil, and the time of danger is past.

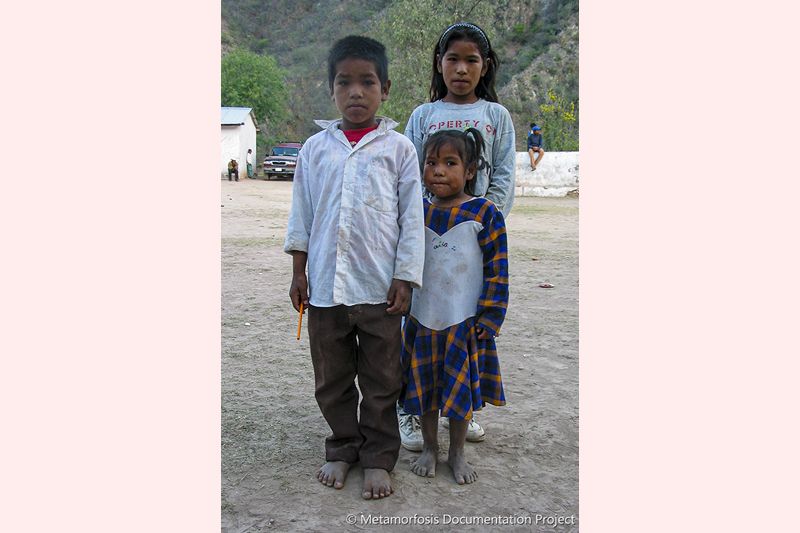

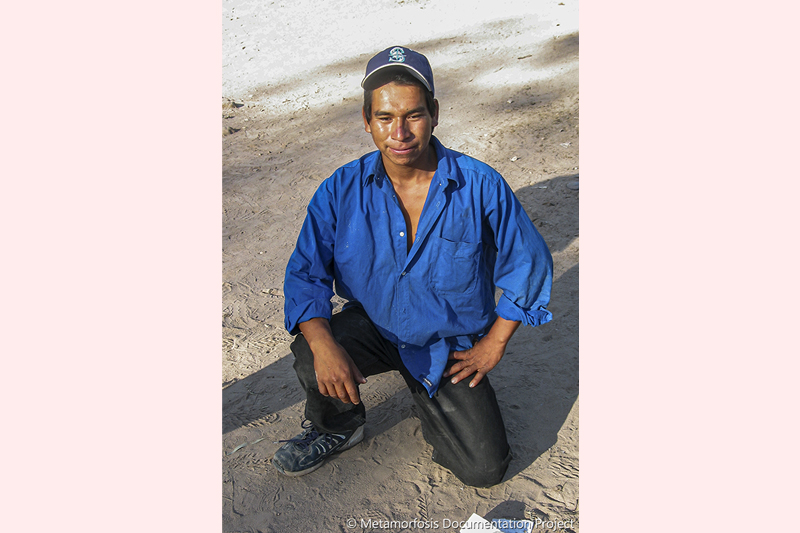

At first the members of the community were apprehensive about the camera. Outsiders had come and photographed them several times, but they had never been able to see and keep their photos.

The magic of the instant image in the digital camera's viewer and our offer of promptly giving them hard copies quickly gained their interest. We spent hours every night printing from our laptop, making sure their pictures were ready for the next day. By Sunday morning everyone in the village wanted their pictures taken. A long line formed - individuals, couples and whole families dressed up for the occasion. They were surprised that the pictures were given to them without charge, and this generosity was reciprocated, with multiple invitations to witness ceremonies and share in the events.

Since the day we arrived and the villagers noticed our cameras, they started asking if we knew Nicolás. "El mentao Nicolás" (The so-called Nicolás), as they referred to him, was a guy from Mexico City who had come the year before and promised to return and bring back the photos he had taken during his stay. He had not returned.

Every once in a while someone would come up to us and ask, "Did el mentao Nicolás come with you? He promised us photos." So we thought it would be fitting to refer to our bringing back the photos for them as "Yo no conozco a Nicolás (I don't know Nicolás)". A month after our first visit, we returned to the village with good prints of the photos and made an improvised art exhibit, placing one hundred and eight photos on the outside wall of the church for the villagers to enjoy. Just before dusk we invited them to take down the photos and keep them. After dark we projected the video of the ceremonies on the church wall for them to see; it was also the first time they had seen their dances as spectators.

It is our hope that by sharing with them the results of our documentation, this village will be better empowered to preserve their culture and that their transformation in the postmodern world takes place more on their own terms.